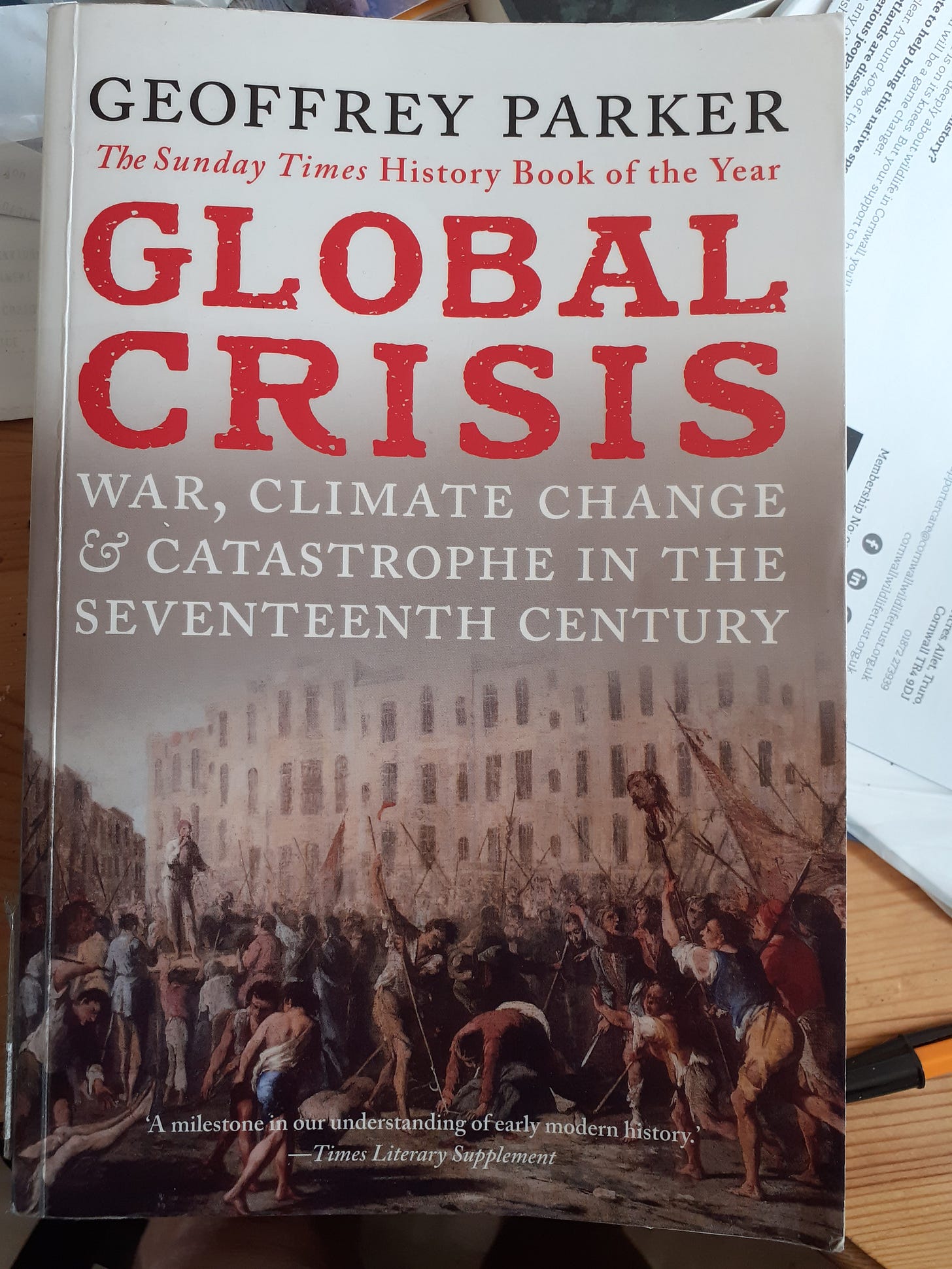

Review. Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the 17th century by Geoffrey Parker

752.

My photo

I have to warn you that this erudite and fascinating book is the size of a breeze block but while being exhaustive is not at all exhausting. Or at least, I didn’t find it so. It’s well-written and has bountiful graphs and diagrams for nerds like me. I have only one criticism and that is that I sometimes got lost amongst all the bloodshed and revolts led by fanatical doomed teenage boys. I found it gripping and terrifying in equal measure.

As Geoffrey Parker explains in his Prologue “Climate Change has frequently caused or contributed to widespread destruction and dislocation on Earth... in the mid-fourteenth century, a combination of violent climatic oscillations and major epidemics halved Europe’s population and caused severe depopulation and disruption in much of Asia... [I]n the mid-17th century, the Earth experienced some of the coldest weather recorded in over a millennium. Perhaps one third of the human population died.”

Geoffrey Parker mainly looks at Europe and China. He narrows the focus to the time between 1618 and 1850 and copes with the huge number of rebellions, revolts, riots and wars in the 17th century all over Europe.

The ruling classes of 17th century Europe seem to have believed that if the weather was frightful and the harvest bad, the best thing you could do was attack another country or several. If there wasn’t another country easy to attack, as in England, then the thing to do was to have a civil war.

Almost all these wars were motivated in one way or another by religion. Catholics and Protestants hammered each other all over Europe; armies marched, cannon bellowed, the poor starved and died and the best thing all the different monarchs could think of to do, was to start another war. Preferably with fellow-Christians who believed something slightly different. In the period between 1618 and 1680, Poland was at peace for only 27 years, the Dutch Republic for only 14, France for only 11 and Spain for 3 years.

Over and over again, by the time the different states had run out of money for war (despite high taxes on the poor), the populations of their countries had gone down by around a third to a half. Most of those will have been famine or disease deaths. No European aristo ever seems to have realised that killing off a lot of peasants would make the ruling classes poorer and weaker.

As Europe and China descended into chaos, one place in the world experienced the Little Ice Age but dealt with it differently. This was early Tokugawa Japan. There had been much war in Japan – the late 16th century ended the time known as the Warring States Era. By that time, there was only one focus of power, the Tokugawa dynasty and its allies. Japan was reunited by three powerful warlords, the last of whom, Tokugawa Ieyasu, got the title Shogun from the emperor in 1603. He and his son Hidetada and grandson Iemitsu then proceeded to pacify the country ruthlessly and intelligently. They were the model of what an authoritarian government could be if it wasn’t generally led by psychopaths, sociopaths and narcissists.

The global crisis came to Japan in the form of the Kan’ei famine. The price of rice quadrupled between 1633 and 1642. A massive revolt at Shimabara in 1637, mainly caused by taxes imposed by the local lord, was led by Amakuso Shiro, a 16 year old boy who claimed to be the reincarnation of Jesus Christ. An army of over 100,000 men sent by the Shogun Iemitsu destroyed their castle and slaughtered everyone within, including Amakuso Shiro.

On the other hand, the Shogun set up food kitchens and shelters for the starving and instructed all daimyo and city magistrates to do the same. He authorized the release of rice held in government granaries for food and for seed grain. He drastically reduced the state’s tax demands. The records of one village showed that it paid to the central government 23% of its total production in 1636 but by 1642 it was only paying 6%.

In 1642 he received accusations that some granary officials and rice merchants were withholding rice reserves in the hope of getting a better price. Iemitsu had eight of them executed, required four others to commit suicide and exiled many more after confiscating their property. The hoarding ceased.

Japan maintained its isolationism until 1853 when navies arrived from states that had developed much better military technology, mostly through unrelenting war. There had been relative peace and prosperity in Japan, even for the peasants, for the previous 200 years.

What a radical notion: don’t go to war, look after your people.

Now Climate Change is coming for us again.

The 17th century crisis of cooling in Europe seems to have been caused by a period of reduced sunspots - the Maunder Minimum - and increased volcanic activity – there were dust veils produced by twelve known volcanic eruptions around the Pacific between 1638 and 1644. There were more frequent El Ninos. Perhaps there was also a drawdown of CO2 in the atmosphere caused by the megadeaths from smallpox and measles of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas and the consequent regrowth of the forests that had been cut. Given a few decades, trees can sequester an awful lot of carbon which does cool the Earth.

What seems clear from the records of the 17th century climate crisis and our modern climatic polyshambles is that the climate doesn’t like to shift. If you change the temperature of the Earth, even if only by an average 1 or 2 degrees C up or down, the weather reacts, whiplashing from drought to wildfires to floods to hurricanes and back again. Obviously this is what’s happening now as we amble into the future arguing that climate change is natural and we should stop worrying about it.

I’ll say it again. A third to a half of the population of Europe and China died in the worst part of the crisis from 1618 to 1680.

Four billion corpses? Is that what we want?

~~~